23rd JULY 2015 DR. BABURAO PANDURANG PATEL ( PATIL ) BIOGRAPHY AND REVIEWS

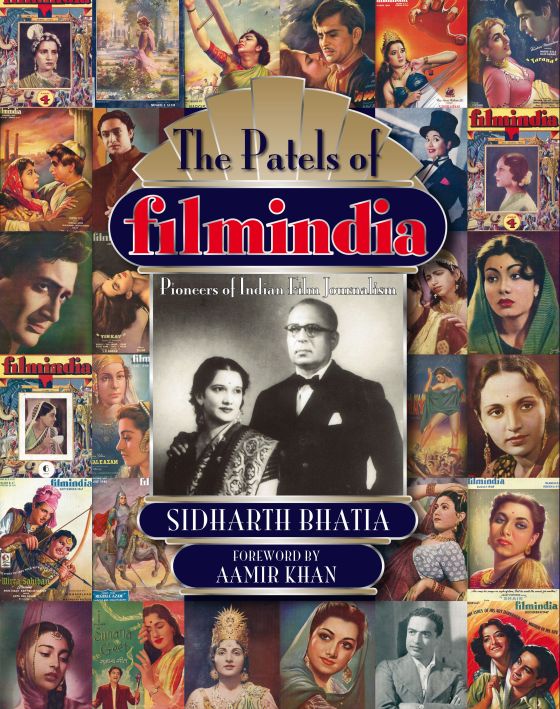

Book Review: Sidharth Bhatia’s ‘The Patels of Filmindia: Pioneers of Indian Film Journalism’

22

I have a confession to make: despite my love for cinema, I’ve never been too keen on film magazines. When I was a child, my parents never bought film magazines, and by the time I’d grown into my teens and had the freedom (and pocket money) to buy whatever reading material I chose, all my major interest in films had shifted to films made before I’d even been born.

As a result, I never knew of Filmindia (or, as it was later renamed, Mother India) until a few years ago, when I read, on Greta’s blog, about Baburao Patel and his film magazine, Filmindia. Reading excerpts on Memsaabstory from Filmindia (and, more often than not, snorting out loud at Baburao Patel’s irreverence), or gushing over the fabulous artwork, I couldn’t help but think:if there’s ever one film magazine I would want to read, it would be the erstwhile Filmindia.

When I heard that Sidharth Bhatia was going to be releasing his book on Baburao Patel andFilmindia, I knew this was right up my alley. Not so much for Baburao Patel (who, I had convinced myself, after having read some of his writing, I did not like—not a nice man), but for the art, the ads, the feel of the 30s, the 40s, the 50s. Even the 60s. The golden age of Hindi cinema. That—the cinema—was what I wanted to read about, what I wanted to see.

Bhatia’s book, The Patels of Filmindia: Pioneers of Indian Film Journalism (2015; Indus Source Books, ISBN: 978-81-88569-67-0; 171 pages; Rs 2,000), however, came as a revelation—because it had me deeply engrossed not just in its many excerpts from Filmindia, but in the lives of Baburao Patel and his wife Sushila Rani Patel too.

The first ten chapters of the book trace the lives, both personal and professional, of Baburao Patel and Sushila. Born in 1904, Baburao came to Bombay as a boy when his family shifted to the city, and after a while left off studying formally (though he remained a voracious reader all his life). A brief stint in cinema—as script writer and director—followed, until 1935, when, along with the owner of the New Jack Printing Press, he launched Filmindia. There was no looking back, then: Baburao Patel went from strength to strength, fearless, brusque, and outspoken in his editorials (and most of the articles and film reviews, which he wrote himself).

There are a couple of chapters about Baburao’s pursuit of Sushila (whom he launched in a film and later married—even though he was already married and was nearly 14 years older than her). There are interesting anecdotes about the Patels’ relationships with the who’s who of Indian society—and not just the film world—of that period, of the love-hate relationships, too, with everybody from Noorjehan to KA Abbas to the Anands of Navketan. Baburao Patel and Sushila (who took over her fair share of Filmindia work) were not merely the people who edited and ran India’s best-loved film magazine; they were, obviously, stalwarts in their own right. Worthy enough for Baburao Patel to stand for elections, to win, to convert his magazine from a cinema-oriented one to a mix in which politics dominated.

Following the biographies of Baburao, Sushila, and the magazine they ran for 50 years (Filmindia, later named Mother India shut shop in 1985) comes the magazine itself: 80 pages of reviews, articles, and Question and Answer sections from various issues of Filmindia/Mother India. The reviews range from those of films long forgotten, even lost (like Navketan’s Afsar) to films that are still admired and loved, like Anupama, Devdas, and Kaala Bazaar. The articles run the gamut from ‘howlers’ (Baburao’s word, not mine) from the cinema industry to more general observations on what was wrong (and occasionally, right) with Hindi cinema. Interspersed with the text (which includes images of the original article, as it appeared in the magazine) are lots of images—photographs, advertisements for films (and for other products, ranging from thermos flasks to Lux), and more.

Sometime back, Anu and I were discussing the idea of people dismissing a film because a character (especially a protagonist) is portrayed as less than perfect. Both of us had been of the opinion that a character’s morality (or lack of it) shouldn’t take away from the worth of the film. After all, all stories need not be pretty, and all characters need not be noble and nice.

I was reminded of that while reading this book. Baburao Patel, for all his charisma and fearlessness, comes across as just the sort of person I’d want to steer clear of: rude, sexist, at times bigoted and regressive, hypocritical (to read his fierce indignation about morality as shown onscreen, one would imagine the man to be a saint in his personal life, not the trigamist and serial philanderer he actually was), and—well, generally not likeable. (I will not dwell on his writing, the style of which doesn’t appeal to me—it has an odd, sometimes ungrammatical feel to it that sounds more like Hindi film dialogue translated into English).

Despite that, I’d call this book a keeper. Sidharth Bhatia does a brilliant job of showcasing both the Patels and their creation. The biographies are well told, not too gossipy, not too lengthy. The excerpts chosen for the latter half of the book are well-selected, with an equal mix of well-known films and obscure ones, and films that Baburao lambasted (“C.I.D., in brief, is a tolerably well produced and directed, but cheaply and stupidly conceived, unpalatable crime picture”) to those on which he showered praise (“…Chaudhvin ka Chand is the scintillating result of a rare combination of a good story and skillful presentation…”).

And the images. Nargis and a young Dilip Kumar. Madhubala (a Patel favourite—Sushila Rani Patel taught her English). Durga Khote, Ashok Kumar, Sushila Rani herself in and as Draupadi. Dev Anand. Suraiya, Noorjehan, Raj Kapoor. And dozens of others now long-forgotten. Stills from films, photos from parties and events (Pandit Nehru with Sushila Rani, for instance).

A treat, that’s what this is. And you get to meet two people whose lives could well be the basis of a pretty entertaining film.

You can buy The Patels of Filmindia: Pioneers of Indian Film Journalism here, on Amazon India

Patel rap

It wouldn't be right to call Baburao Patel, editor-publisher of filmindia, a gossip columnist. He was more a reviewer. But his fabled snark dwarfed even Devi's and set the tone for the kind of writing one saw in columns over time. filmindia's three columns, Bombay Calling,You'll Hardly Believe That… and Pictures in Making had Patel sign off as 'Hyacinth' or 'Judas'. "The entire mode of gossip is marked by innuendo, and filmindia was a master of innuendo. Most of it was in answers to letters because people wanted to verify rumours they'd heard about stars and studios. Sometimes, it would appear in the Studio Notessection," informs Neepa Majumdar, author of Wanted Cultured Ladies Only, a book on Indian cinema and actresses of the 1930s-1950s.

Patel's deadpan, offensive humour, which found an audience in no time, has fans even today. One of them is Greta Kaemmer, a vintage Hindi film buff and blogger atMemsaabstory who scans whatever filmindia copies she gets her hands on. "Stardustmagazines from the '70s were gleefully gossipy, but filmindia is my all-time favourite because of Baburao's wit. Today's film columns are poorly written and researched, and mostly unimaginative," she feels.

(An April 1957 celeb descriptor from filmindia's Pictures in Making column. Nirupa Roy was one of the many Baburao Patel loved to pick on. Source - Memsaabstory)

It's an opinion shared by film historian SMM Ausaja, who says Patel's vitriol was not only extreme, but also taken sportingly by most: "When V. Shantaram's Jhanak Jhanak Payal Baaje was released, the (review) headline Patel used was 'Mental Masturbation of a Senile Soul'. He said Prithviraj Kapoor was an 'uncouth Pathan who shouldn't be in the industry', that Dilip Kumar looked like 'an escaped prisoner' and Kishore Kumar reminded him of a monkey. But they took it in their stride." Of course, there were exceptions. "Patel once said something that angered (actress) Shanta Apte so much that she went to his office and slapped him," Ausaja says.

Baburao Patel went on to become founder-editor of the political magazine Mother India, establish a homeopathic company called Mother India Pharmaceuticals and member of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh (now BJP). But it's filmindia that he remains synonymous with.

(Baburao Patel being snarky like only he could. The 'victim' here was Padmini. Source- Memsaabstory)

Bachchan's boycott

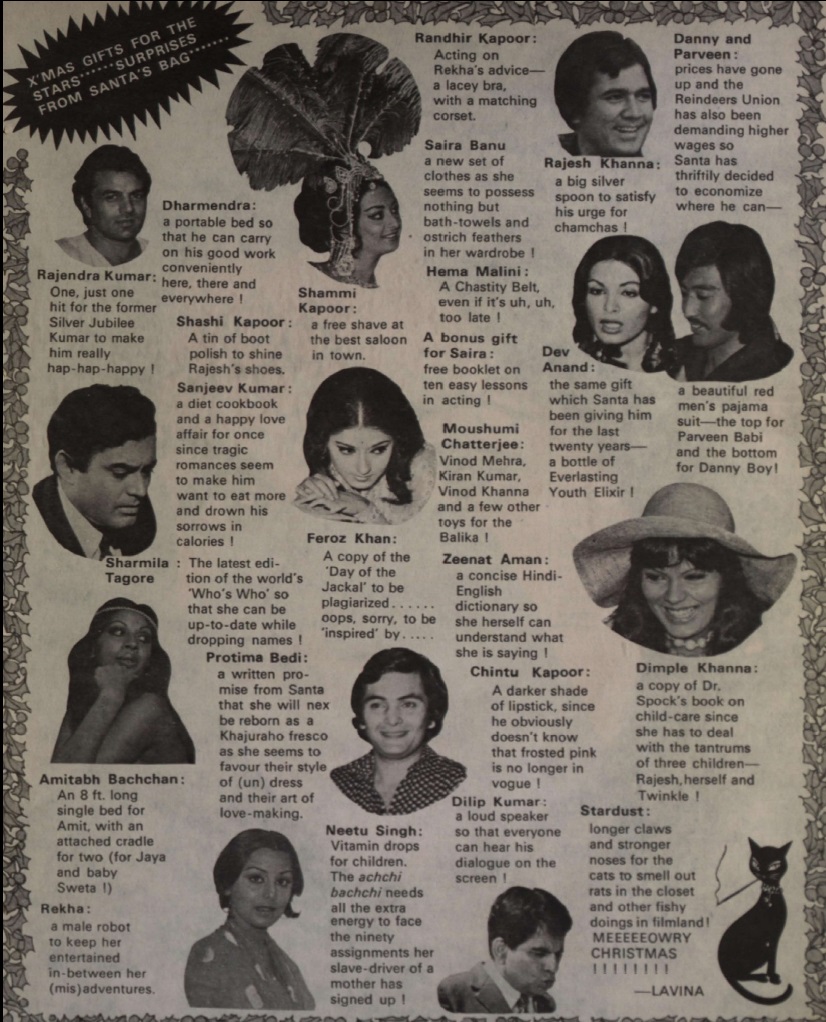

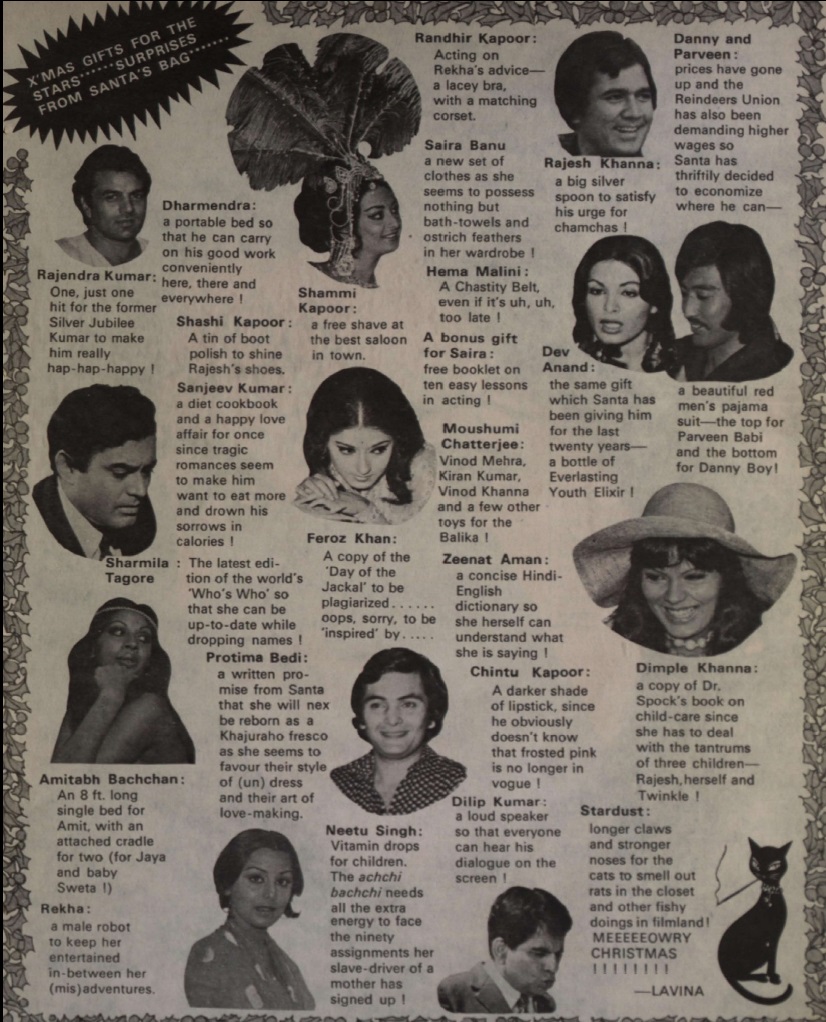

Writing about gossip without mention of Nari Hira's Stardust is like Thanksgiving without cranberry sauce. It was not only the cult Neeta's Natter column, but the magazine as a whole that catapulted gossip to astral levels. The nicknames it gave people – from 'La Tagore' for Sharmila Tagore and 'Mumu' for Mumtaz to 'Garam Dharam' for Dharmendra and 'Chi Chi' for Govinda – became Stardust's calling card. "Stardust projected familiarity with the stars and caught on like no other film magazine ever had," says film journalist Dinesh Raheja. Not least for the way in which it bared the stars of the day.

(Neeta's Natter- 'Gifts for Stars'. Source- Jai Arjun Singh)

Dr. Baburao Patel, was not only a brilliant writer but also a seeker of knowledge and in the early forties, he mastered the art of healing the sick through Homoeopathy and made me also a homoeopath alongside with him. Together we started the Mother India Pharmaceuticals Pvt. Ltd in 1973 with our long first hand experience of patients in hundreds. Mother India Pharmaceuticals Pvt. Ltd. is now well-established, not only in Indian cities but also has users in other parts of the world.

At 93, I am still under the spell of MIP Products to keep me physically fit and mentally active. I never miss MIP Shiv Shakti tablets. They are the secret of good health. People often wonder at the number of various things I do in a day, apart from singing and teaching music and organizing musical concerts. When my friends want to know the secret of my smooth complextion, my reply is "Moonbeam Cream". For a back pain only caused by undue strain, only "Magic Touch" is the cure. As regards "Life Saver" it is always in my handbag. "Cosmic Saver" for the hair is another delight. The list is endless.

Dr. U. Ravi Rao, my nephew, is full of ideas, and an expert pharmacologist. He has been assiduously trained in homoeopathy, learnt under Dr. Baburao Patel. I wish and pray for his success.

MIP has a wonderful future for MIP Pvt. Ltd. to spread its wings far and wide with this website. Heartiest congratulations for this interesting website.

Dr. Sushila Rani Baburao Patel

Dr.Baburao Patel's book of "Homoeopathic Life Savers" and remedies are well known. In fact, they make him immortal. I have been using these remedies for a long time. Some of them are remarkably effective.

His "Shiv-Shakti" is for vim, vigour and vitality. It is a boon to every man, woman and child. "Moonbeam" is an all purpose complexion cream and a face beautifier. My wife Savita uses "Magic Touch" to get relief from knee joint pain. Reports say both "Eye Bright" and "Tonsils" are a blessing. Personally, I rate "Life Saver" as the best product which indeed meets 100 emergencies. It is like having a doctor in our pocket, especially while travelling. I pray to God that this unique remedy will be available in every home, in every country in the world. For this great humanitarian noble work, we are eternally grateful to Girnar Mother Dr.Sushila Rani Patel, the woman behind Dr.Baburao Patel's pioneering work of 50 years healing experience. Heartiest greetings to the family of Dr.U.Ravi Rao for taking over Mother India Pharmaceuticals and continuing the show with improvement.

K.B. Lal

Dr.Baburao Patel's book of " Homoeopathic Life Savers" and remedies are well known. In fact, they make him immortal. I have been using these remedies for a long time. Some of them are remarkably effective. His Shiv-Shakti" tonic is for vim, vigour and vitality. It is a boon to every man, woman and child. "Moonbeam" is an all purpose complexion c...

K.B. Lal

Dr. Baburao Patel, was not only a brilliant writer but a seeker of knowledage and in the early forties, he mastered the art of healing the sick through Homoeopathy and made me also a homoeopath alongside with him. Together we started the Mother India Pharmaceuticals Pvt. Ltd in 1973 with our long first hand experience of patients in hundreds. Mo...

Dr. Sushila Rani Baburao Patel

Search MIP Website

Testimonials

Dr.Baburao Patel's book of " Homoeopathic Life Savers" and remedies are well known. In fact, they make him immortal. I have been using these remedies for a long time. Some of them are remarkably effective. His Shiv-Shakti" tonic is for vim, vigour and vitality. It is a boon to every man, woman and child. "Moonbeam" is an all purpose complexion c...

K.B. Lal

Dr. Baburao Patel, was not only a brilliant writer but a seeker of knowledage and in the early forties, he mastered the art of healing the sick through Homoeopathy and made me also a homoeopath alongside with him. Together we started the Mother India Pharmaceuticals Pvt. Ltd in 1973 with our long first hand experience of patients in hundreds. Mo...

Dr. Sushila Rani Baburao Patel